...all the days and nights by Doug DuBois

It is hard enough to photograph your family let alone to be honest about it. At worst, the images are pure falsity on the part of the photographer that rely on visual descriptions of natural beauty or grace - usually the most tiring of domestic cliches. The best unlock that which is powerful enough to make you wish you could curl back up into fetal position hoping for some comfort. Doug DuBois' new book from Aperture ...all the days and nights is the latter.

DuBois has been photographing his family since 1984. A few of the photographs have trickled out over the past two decades, some in MoMA's The Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort show and in Doubletake magazine, but mostly they have remained unseen but by the lucky. Lucky because this memoir, for lack of a better term, is weighted with an unflinching gaze that risks acquiring too much knowledge both on the part of the photographer and the viewer.

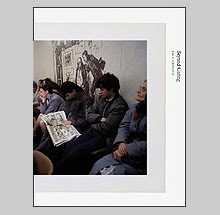

The narrator of memoir projects onto its subjects, and photography is good at amplifying and projecting. DuBois' story is cast with two main characters, his parents. Although many images show his siblings, the central spotlight is on mother and father. The book opens with quiet, everyday domestic tranquility; the father fiddles with a suitcase illuminated with a play of light; a daughter worries over her groomed appearance while the reality of her room is complete chaos; the parents are happy together having drinks - the mother reacting to the flirtations of the father. They are minor events of small gesture which, to a lesser attentive narrator, would certainly not have triggered the same instincts to record.

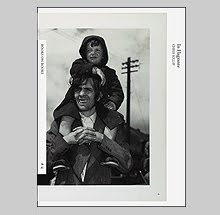

Eight photographs in and the tranquility is disrupted by event - the father is hospitalized with major injuries that we learn were sustained from a near-fatal fall from a commuter train. It is here that the book takes a momentary dangerous turn towards a literal narrative and purpose. Lucky again that DuBois knows to quickly steer back to the quieter, less obvious moments that are leaden with the unspoken.

During the father's convalescence, it is impossible not to notice the constant state of inner reflection on the mother's face. Her intense and sullen expressions transcend concern for the father's condition pointing rather to a deeper psychological wound that has opened. Never again do we witness a smile or lightness of being in her. Every photo there after is an individual portrait. The few times when the parents are in the same frame the estrangement resonates clearly. By book's end, the split is clear.

...all the days and nights is broken into two parts. DuBois made these images during two working periods, the first from 1984-1990, the second from 1999-2008. The sequencing and edit are well handled as is the printing and layout. The introduction by Donald Antrim, a regular contributor to The New Yorker, is with full understanding of DuBois accomplishment and beautifully realized.

DuBois' own brief pitch-perfect afterword describes battles with depression and attempts at suicide on the part of his mother. It also describes his role as memoirist for his family and the truths the photos reveal. His father asks, "Was it really that bad?" when he first sees a mock up of this book. All along one senses that where ever the underlying tension in DuBois' photos was coming from, reality was probably far worse for each of the players. Photography can act as a mask just like a person's countenance yet what DuBois is willing to lay bare in this book is painfully clear.

"Was it really that bad?" The strength of this work is, with all we have been privy to -- all of the intrusion and embarrassment that comes with Dubois inviting us into the household -- we might presume to answer for one of the characters.